Article by: Hari Yellina

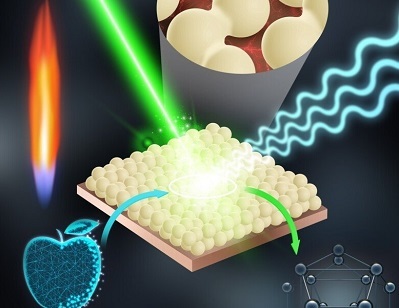

In just a few minutes, researchers at Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet have developed a small sensor for detecting pesticides on fruit. The approach, which was described as a proof-of-concept in the journal Advanced Science, uses flame-sprayed silver nanoparticles to boost chemical signals. While the research is still in its early stages, the researchers believe that these nano-sensors will be able to detect pesticides in food before they are consumed.

“Reports show that up to half of all fruits sold in the EU contain pesticide residues that have been linked to human health problems in larger quantities,” says Georgios Sotiriou, principal researcher at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell Biology and the study’s corresponding author. “However, present methods for detecting pesticides on specific products prior to consumption are limited in practise due to the high cost and time-consuming fabrication of its sensors.” To address this, we created low-cost, repeatable nano-sensors that might be used to monitor residues of pesticides in fruits at a supermarket, for example.”

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering, or SERS, a strong sensing technology that can boost the diagnostic signals of biomolecules on metal surfaces by more than 1 million times, is used in the new nano-sensors. Chemical and environmental studies, as well as the detection of biomarkers for various diseases, have all benefited from the method. High cost of production and limited batch-to-batch consistency have, however, limited their use in food safety diagnostics so far.

The researchers used flame spray to deposit small droplets of silver nanoparticles onto a glass surface to build a SERS nano-sensor in this study. Flame spray is a well-established and cost-effective approach for depositing metallic coatings. “The flame spray may be utilised to swiftly manufacture consistent SERS films across wide areas, removing one of the fundamental impediments to scalability,” says Haipeng Li, the study’s first author and a postdoctoral researcher in Sotiriou’s team. The researchers calibrated the sensors to detect low quantities of parathion-ethyl, a hazardous agricultural insecticide that is prohibited or restricted in most countries, to evaluate their practical application.

A little amount of parathion-ethyl was applied to an apple portion. Later, the residues were collected using a cotton swab soaked in a solution to breakdown the pesticide molecules. The pesticides were detected when the solution was sprayed on the sensor. The researchers now want to see if the nano-sensors can be used in other areas, such as finding biomarkers for specific diseases at the point of care in resource-constrained environments. The European Research Council (ERC), Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SSF), and the Swedish Research Council all contributed to the study.